Recently physicist John Hilborn donated a copy of the front page of the Pembroke Observer from 1957 Nov 4, which trumpeted “RUSSIANS … INTO SPACE, CANADA … INTO RESEARCH” with a one-inch headline. The article described how the USSR launched Sputnik-2 into space (with the doomed dog Laika on board), on the same day that Canada’s National Research Universal (NRU) reactor first operated at Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories.

Artifacts chair Jim Ungrin framed the fragile page and displayed it in the “NRU shrine” at the Canadian Nuclear Heritage Museum (CNHM, 51 Poplar St, Deep River). Visitors can also read the small article at the bottom of the page “CARRIED RADIUM, Others May Be Affected” regarding a peculiar incident in Toronto, one completely unknown in our nuclear history circles. On-line newspaper archives (Toronto Star, Montreal Gazette and the New York Times) added further details.

The element radium was first discovered 125 years ago on 1898 Dec 21, by Marie Sklodowska-Curie and her husband Pierre Curie in their laboratory in Paris. It is a rare “daughter product” of both uranium and thorium decay chains, occurring at about 1/7 of a gram per tonne of uranium ore. Radium gives off alpha particles, along with penetrating gamma rays, and is far more radioactive per gram than the host uranium. One of the original quantifications of radiation was the “Curie”, the amount of radiation (37 GBq) given off by one gram of radium, a unit still widely used today.

The quest for radium led Gilbert and Charlie Labine, of Westmeath Ontario, to discover and establish the Port Radium uranium mine in the Northwest Territories in 1930, and subsequently to build the radium refinery at Port Hope. Radium, when concentrated and refined into a pure metal, was worth $70,000 per gram in 1930 (about $1.25 million today); its value was due to its high-energy gamma emissions, which were sufficiently penetrating to use for cancer treatment. In 1930, Canada had a total of 16 grams of radium in its hospitals, but this was insufficient to meet the demand.

Radium can also be mixed with certain compounds in small amounts, making a luminescent paint for glow-in-the-dark applications like wrist watches, clocks and aircraft instruments; both the CNHM and the Canadian Clock Museum have old radium-painted clocks, and they still set a Geiger counter clicking rapidly. A lack of knowledge and gross criminal negligence led to the injury and deaths of a number of young women (“Radium Girls”) employed to paint these items, but that is another well-documented story.

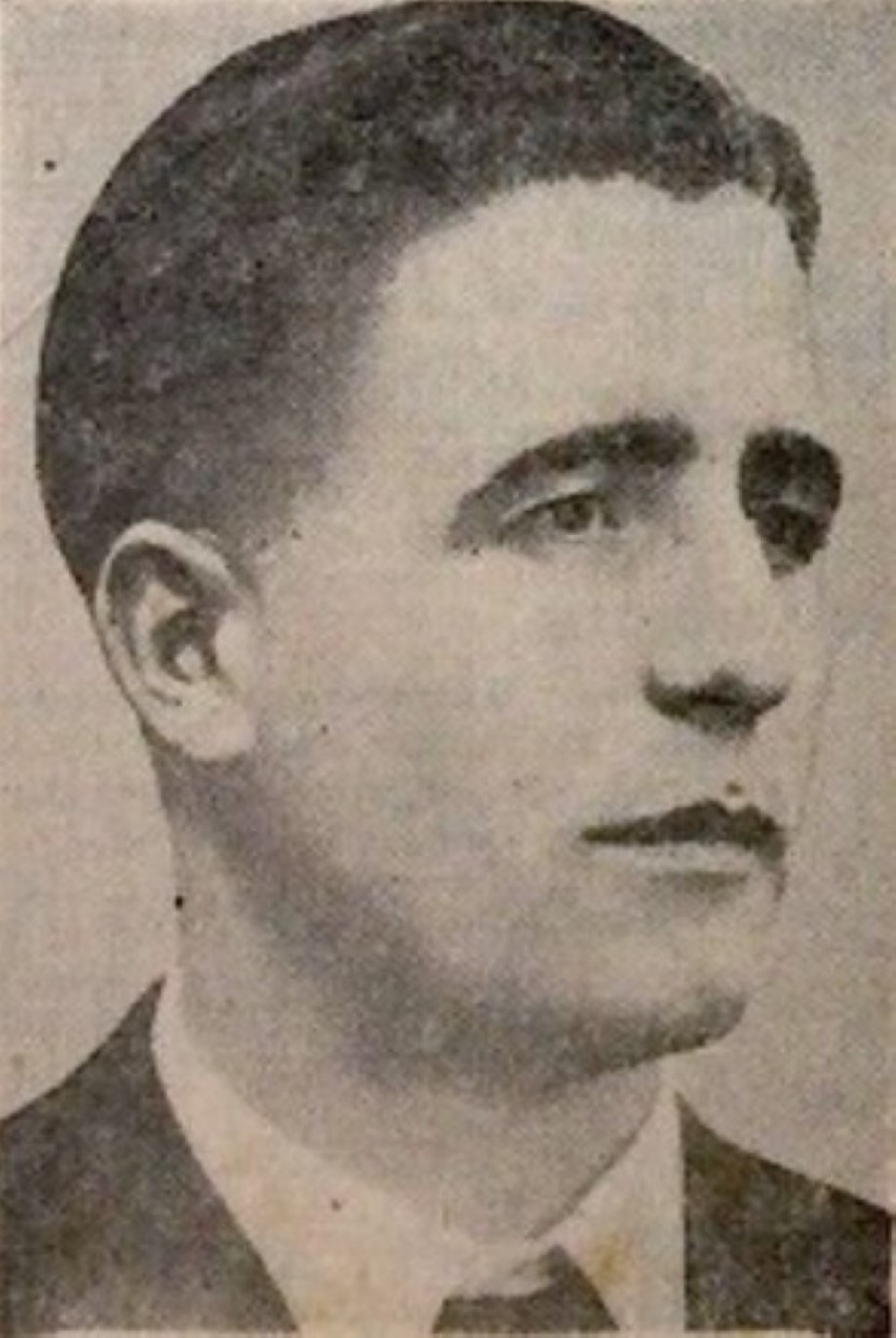

Now to Toronto’s radium-man story. By this date, radium had largely been supplanted by the panoply of artificial radioactive material generated in nuclear reactors. However, there were still stocks of radium paints around, as would cause considerable trouble in Toronto’s “radiation scare” of 1961 June (again, another story). In 1957 Nov a recent West German immigrant mechanic, 29-year-old “mild-mannered” Gunder Kuhn, had a vial containing 20 g of a radium compound stolen from his former employer in Germany; he had brought it to Canada to paint watch dials and instruments in his spare time.

On Nov 3 Kuhn was a spectator at a civil defence drill at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) grounds west of downtown Toronto, where police officers were being trained in the use of radiation detection equipment. Presumably Kuhn had some misgivings about the vial’s radioactivity, because he went to his boarding house, retrieved the vial, and presented it for examination by the officers. The Pembroke Observer stated “A policeman a few feet away pointed his Geiger counter at the German. The indicator swung wildly right off the dial.” Kuhn was searched and promptly arrested for carrying a loaded and unregistered “7.65 Walther pistol in his coat pocket”. He was then “hustled off to the Don Jail and given a decontamination bath while police and civil defence agents spread out to run down the radioactivity in his wake.”

Kuhn’s clothes were burned at the jail, along with his bedding; this sounds ludicrous, as the ash and off gas from the fire would have spread the radiation (you cannot burn it to destroy radiation). Similarly, the other nine occupants of the Jameson Avenue rooming house “were advised to wash with soap and water to neutralize any radiation. All those living at the rooming house and policemen who came in contact with Kuhn were to be given blood tests.”

Initial reported readings of the vial indicated an exposure of “50 roentgens”, presumably per hour. This is a very high radiation rate, and several reports reported “Forty in a single dose is considered fatal”. Thankfully, the dose was misread or misreported by a factor of 1000; the Montreal Gazette later reported that the radium vial “emitted 52 milli-roentgens an hour.” However, it was unclear as to how much total radiation Kuhn had absorbed, although the NY Times reported “a medical check showed no trace of radioactivity in his system”.

So, what became of Kuhn? The “husky immigrant [said] It’s a great relief. I’m sorry this happened. I never realized I was putting people in danger.” He planned to visit his wife and infant daughter in Lubeck, West Germany, for Christmas. I hope he made it.